Why Gurdon (Still) Doesn’t Get It: Parent-Vision, Teen-Vision, and What It Means For Books to Reach Their Audience

An alternative title to this post might be, “YA saves, but not like you think.” It’s about how the shouting match over “darkness” in YA has its roots in two very different ways of seeing the books in question (and the business of teens reading). I also fight my way toward an articulation of what’s a little off for me with the direction the #YAsaves conversation has gone.

Okay, first what’s new: today the WSJ publishes another Meghan Gurdon piece following up on her denunciation of YA as too dark (I blogged about the first one here). Bookshelves of Doom’s Leila Roy responds to Gurdon here with wisdom, wit, and eloquence. Here’s what she says in response to Gurdon’s claim that “It is surely worth our taking into account whether we do young people a disservice by seeming to endorse the worst that life has to offer”:

Sure, there are novels that promote certain beliefs and novels that set out to prove points: Ayn Rand and Beatrice Sparks come to mind. But the idea that a book that deals with rape somehow endorses it, that a book about anorexia endorses it, that a book about self-harm endorses it, that a book about teen pregnancy endorses it?

No. Compassion is not endorsement. Trying to understand is not endorsement. Exploring our world, giving voices to the silent, trying to gain perspective: None of those things are endorsement. Neither is turning a light on in a dark room.

I told you Roy was smart. Another bit worth quoting:

It was unfortunate that Gurdon dismissed the passion of adolescence as “…feel[ing] more dramatic at the time than it will in retrospect”. Because, while in some cases that might be true — it was, at least, for me — it also minimizes what is, at the very least, an extremely emotionally turbulent time. It’s exactly the sort of “Oh, you’ll laugh about this when you’re older” attitude that always made the teenaged — and again, extremely sheltered — version of me want to punch adults in the face.

This final observation recalled for me a brilliant comment on my editor Andrew Karre’s blog post on audience in response to Gurdon’s first article. Andrew shows how Gurdon’s claim that YA writers and editors only understand children “in the abstract” (while parents “love them very specifically”) couldn’t be more off base. Many of us are, after all, parents as well as writers, and even those of us who aren’t parents write with real kids in mind. MG author Peni Griffin writes,

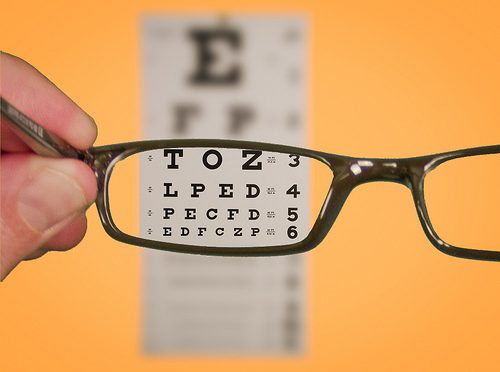

I don’t have any children. I remember my childhood more vividly than the parents I know. There’s a practical reason for this. When I see a kid testing his limits I get double vision, kid vision and adult vision. Say for instance there’s a set of shallow stairs and the kid is jumping them – first one at a time, then two at a time, then three, etc. The kid me is thinking: “Hey, he’s good at that. I wonder how many he can jump?” The adult me is thinking: “That kid is going to break his neck.”

If you’re raising kids, you can’t afford this double vision. You have to act before the kid goes a stair too far. This is why parents and children are in continual conflict – the kid wants to push his limits, the parent wants the kid to grow to adulthood.

When I’m writing for kids, the double vision is an absolute necessity. To interest the kid, I need to see things from his point of view, need to assume competence on the part of child characters, tempering it with the adult view only as appropriate to the realism level of the story. A story that doesn’t let a kid’s growing brain push on its boundaries and exercise its developing synapses won’t engage them in any meaningful way.

Here’s a YA-oriented example: yesterday when I took Liam to the park, I got majorly peeved because a bunch of adolescent males were climbing all over the play structures (as in standing on the roof and jumping from the top of the swing set). The parent in me wanted to know, What right did they have to make the space unsafe for my child?

Consider, though, what a liability that parent perspective is for me as a YA writer. It has to be tempered or silenced before I go to the page or else I won’t be able to voice any of the concerns that are real to the teens in question, among which I might number (for those guys) finding a place for play and identity performance, exploring autonomy, and challenging authority.

Taken together, Griffin and Roy point to the deeper issue beneath Gurdon’s surface complaint about dark themes in YA: the inability of certain parents to accept the validity of other adults (namely YA writers) putting teen-vision before parent-vision. But what makes YA lit so powerful is precisely this decision to let the teen take on life matter more than moralizing.

In my view, YA saves, then–not by presenting a specific content (cutting! discrimination! homophobia! AIDS!), as sometimes seems to be the implication in the #YAsaves conversation–but by voicing varied teen encounters with their world, whatever its contours.